1964 – 1965 Porsche 356C /2000GS Carrera 2 – Ultimate Guide

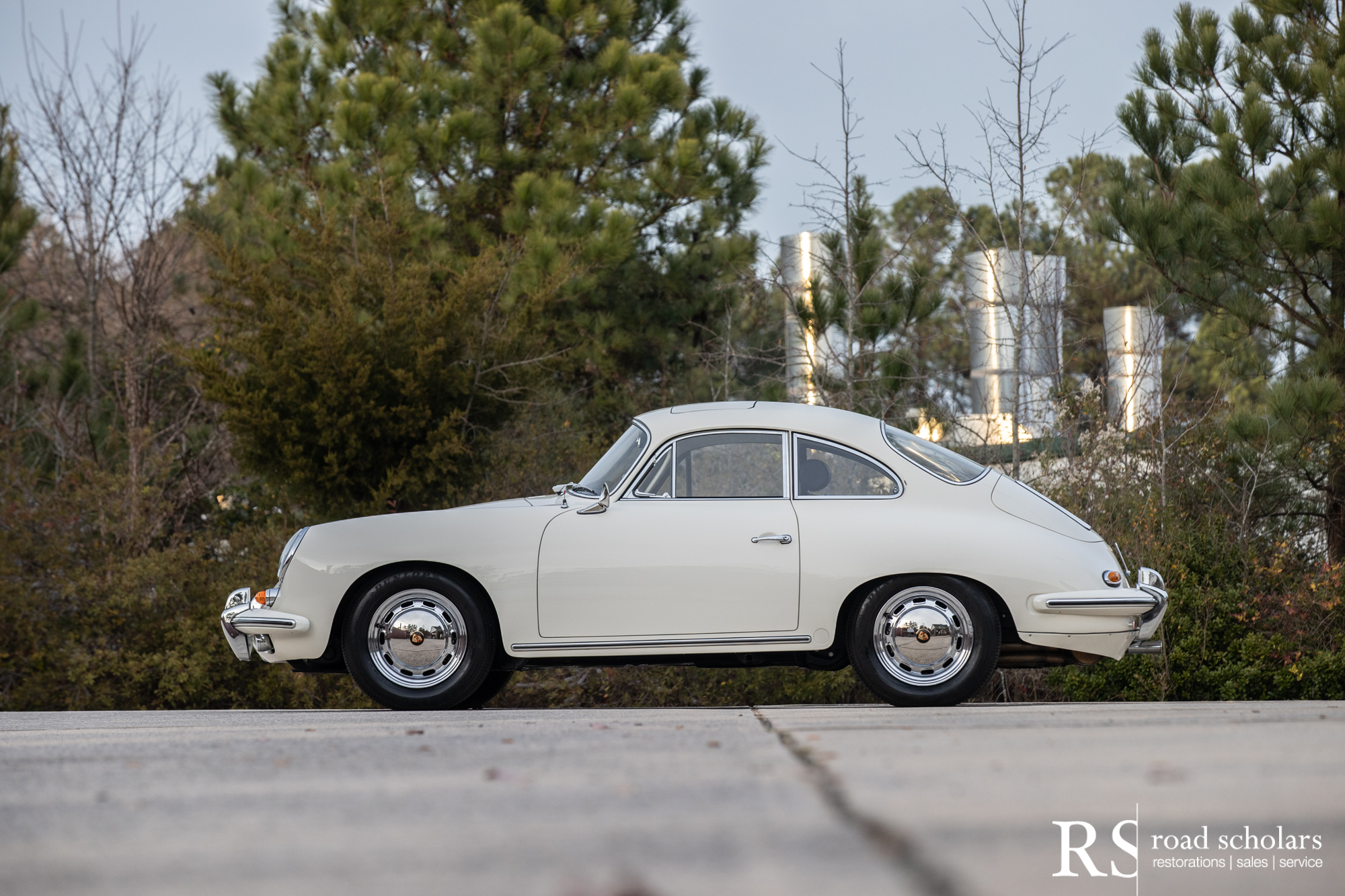

Amongst Porsche 356 enthusiasts, perhaps no model is more coveted than a C-Series Carrera 2. The Carrera 2 represents the culmination of Porsche’s racing technology fitted into a road car package and the ultimate performance-first sports car in the 356 model lineup. The 1,966-cubic centimeter, mechanically complex four-cam Type 587/1 engine was the most powerful unit that Porsche had ever created for a production car, developing 130 brake horsepower at 6,200 rpm; engines modified for competition were claimed to deliver as much as 180 horsepower.

While most Carrera 2s were B models, Porsche installed the 2.0-liter Carrera engine in some T6 steel-bodied C-series Coupes and Cabriolets for the 1964 model year. While the numbers aren’t clear, it is estimated that there were about 101 Coupes and 30 Cabriolet units made. This is one rare Porsche model.

Virtually indistinguishable in appearance from the standard 95 horsepower 356C, the Carrera 2 packed a punch beneath its demure exterior. Its 550 Spyder-derived, two litre, four-cam engine propelled it to sixty miles per hour in 9.2 seconds and on to a top speed of 130 miles per hour, whilst Porsche’s new ATE-manufactured disc brakes and rear transverse leaf arrangement ensured that both braking and handling kept pace with performance.

The 130 bhp, 1,966 cc DOHC air-cooled horizontally opposed four-cylinder engine got two Solex 40 PII-4 carburetors, four-speed manual transmission, independent front and rear suspension, and four-wheel disc brakes. There was no doubt that the Carrera 2000 GS was at the top of Porsche’s product line in 1964. These were very expensive 356s, at a cost of about $7,600 from the factory, nearly twice that of a 1,600-cubic centimeter pushrod-equipped coupe.

According to the reference book by Carrera historians Sprenger and Heinrichs, only 101 Type-C Carrera 2 Coupes were constructed from 1963 to 1965. The coachwork was very similar to that of standard coupes but had a number of subtle modifications. Among them was the use of front bumper guards (without exhaust ports) at both ends. There were also changes to accommodate improved engine cooling, the most important of which was the installation of a pair of small auxiliary oil radiators, mounted one to a side behind the horn grille openings in the nose. The horn grilles themselves were deleted to improve airflow. For reliability, Porsche had adopted a new plain-bearing crankshaft in place of the early Hirth roller-bearing design, which proved fragile as used in previous four-cam engines.

These new Type 587 two-liter motors could be distinguished from the earlier 1600 four-cams by their rectangular camshaft covers and 12-volt electrical systems. The 356 C Carrera was topped by a pair of Solex 40PII-4 downdraft carburetors fed by a single electric fuel pump. The fuel tank was slightly larger (110 liters) than that of the pushrod 356 C. To ease access to the spark plugs, small access panels were installed inside the rear wheel wells. The transmission was a fully synchronized Type 741 four-speed gearbox.

The Carrera’s improved performance mandated better stopping ability as well; 356 C Carreras were equipped with Porsche’s new ATE disc brakes, which had superseded the annular disc arrangement of the 356 B. C-series Carreras had softer torsion-bar springing for greater driving comfort, and a new transverse leaf was mounted below the transaxle to serve as a “camber compensator,” ensuring that the rear wheels never achieved more than slight positive camber. Carreras were tremendously successful in both road racing competition and rallying. Properly set up, they were immensely durable, and given Porsche’s legendary build quality, nearly always finished. Carreras won many international and American amateur racing championships for the marque.

Re the Porsche 356C Carrera 2 article. This comment is incorrect:

“Carreras had softer torsion-bar springing for greater driving comfort, and a new transverse leaf was mounted below the transaxle to serve as a “camber compensator,” ensuring that the rear wheels never achieved more than slight positive camber”

The reason that softer rear torsion bars were used was to counter the natural oversteer characteristics of these cars by transferring load from the outside rear wheel to the outside front wheel. The camber compensator actually kept the effective spring rate of the car the same in terms of comfort when the suspension encountered normal bumps and lumps. It is used in combination with a front anti roll bar. An alternative would be a very stiff front anti-roll bar but this would make the two front wheels less independent of each other.

Unfortunately, due to the swing arms, the limits in camber change were entirely controlled by body roll and squat or lift resulting from acceleration or braking. As Ralph Nader said … unsafe at any speed but using the splines on the torsion bars to set the camber to a few degrees negative in standard position does help limit when things get unpredictable.

0